Morocco

History, Traditions & Capital Cities

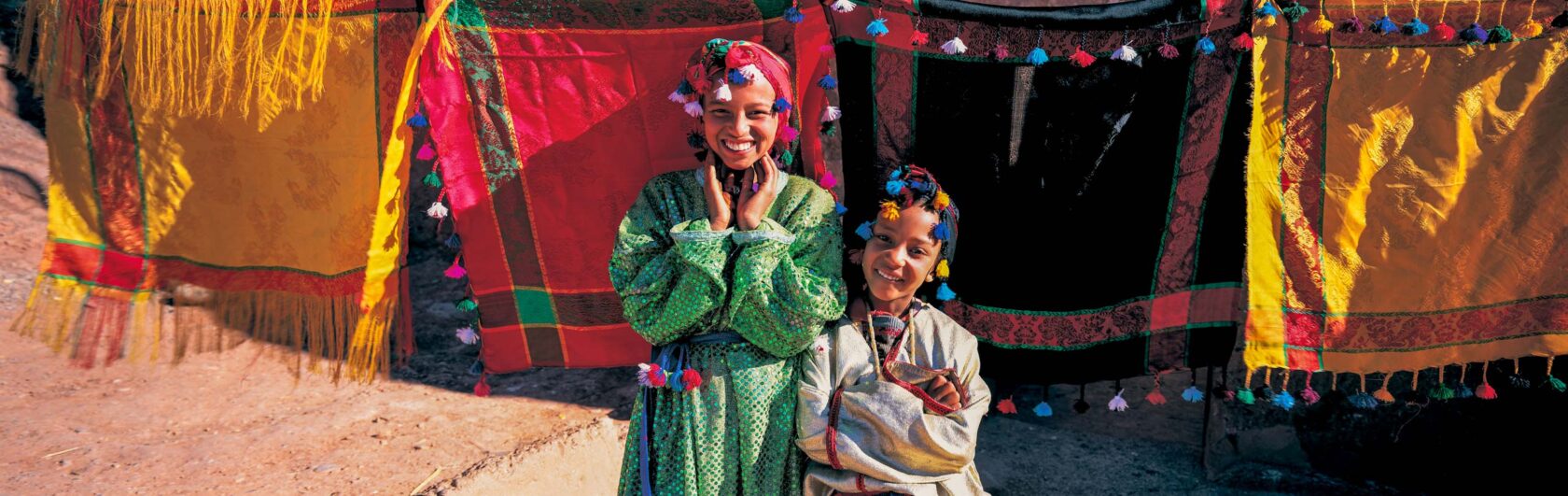

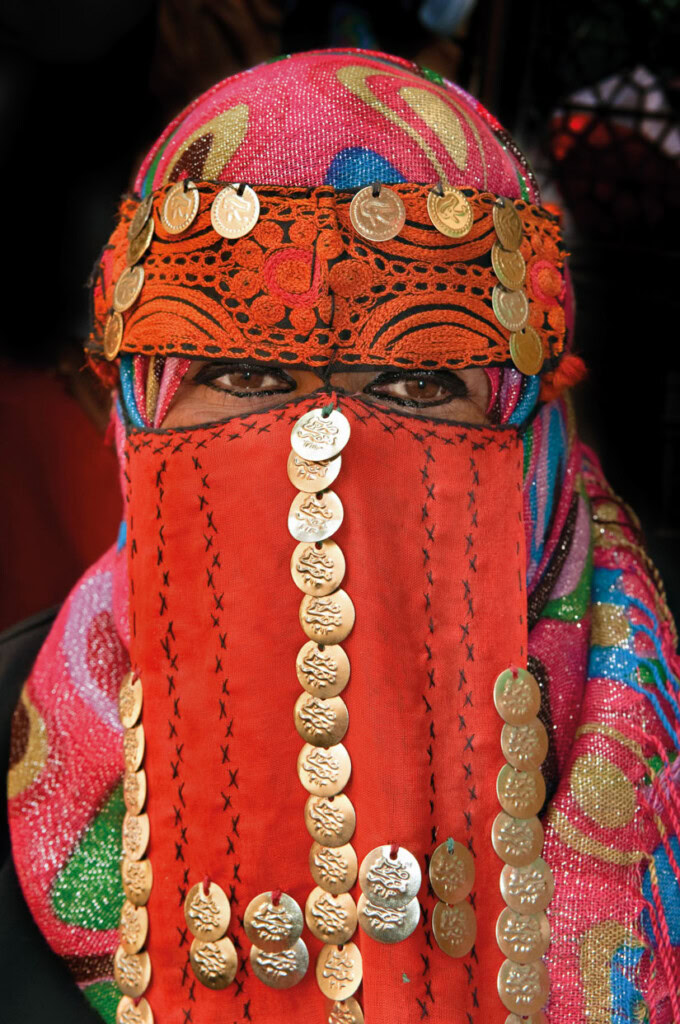

The People of Morocco

Morocco’s original inhabitants were Imazighen (the singular is Amazigh), often referred to by outsiders as Berbers. Their ancestors were both European and Saharan, and arrived in Morocco at various times, settling in the Atlas Mountains. Not a homogeneous group, the Berbers have maintained distinct cultural traditions, and are renowned for their trading activities and the strength of their family and tribal ties.

Jewish presence in Morocco dates back to antiquity; before the founding of Israel there were over 250,000 Jews in the country. While the number has dwindled to a few thousand, Morocco has a fascinating Jewish heritage worth exploring. We’ll see important traces of it in half a dozen of the sites we visit on Camels to Casbahs.

Arabs arrived in the late 7th century, bringing their Islamic faith, which the Berbers adopted. One hundred years later, Moulay Idriss I (a direct descendant of the prophet Muhammad) arrived, founding the dynasty that established Moroccan statehood. He is buried in the city called Moulay Idriss (we visit it on Day 3), which became a revered pilgrimage site and Morocco’s holiest town.

Orthodox Sunni Islam became prevalent in the 12th and 13th centuries; today it is Morocco’s constitutionally established state religion, with the country’s ruler, King Mohammed VI, holding executive, legislative, and religious powers.

Gnaoua Music

The Gnaoua people of western sub-Sharan Africa were originally brought to Morocco by the Berbers as slaves. After the Berbers converted to Islam and abolished slavery, the Gnaoua became part of a Sufi order practicing ritual possession. Today they’re known for their poetry, call-and-response singing, and trance-inducing music, marked by low-toned melodies played on a bass lute, or sinter, and accompanied by metal castanets called karkabas. It is performed at all-night celebrations of prayer and healing, called lila. As Gnawa music has become more mainstream, international performers have fused its core elements with jazz, blues, reggae, and hip-hop. We’ll be treated to the hypnotic rhythms of this traditionally Moroccan cultural expression when Gnaoua musicians perform at our private desert camp.

The Flavors of Morocco

In Morocco we’ll sample delicate couscous, mouthwatering tagines (both are traditional Berber dishes), and perhaps some amlou, a deliciously addictive spread made from almonds, honey, and nutty argan oil. Because of its place on the spice trade route, Morocco’s cuisine is world-famous for its rich combination of flavorings—the aromas of cinnamon, ginger, and bay waft from every medina.

In fact, Berber/Imazighen, Arabic, Andalusian, French, and Jewish foods have all influenced the fabulous fusion we know as Moroccan cuisine. Traditional Mediterranean staples like wheat and olives are important, along with meat, seafood, dried fruits, pickled lemons, vegetables, walnuts, and mint.

There’s plenty of opportunity to learn more about Moroccan cuisine on Camels to Casbahs: in addition to the many delicious meals we’ll savor, we’re treated to a tagine cooking demonstration by the head chef at our luxury desert camp, and we can take part in an optional Moroccan cooking class on our free afternoon in Marrakesh.

Medinas, Souks, Mellahs, Foundouks, Casbahs, and Ksour

The word medina means “town” in Arabic. It refers to Morocco’s old pre-20th century cities, many of them enclosed within defensive walls. A medina has several monumental gates through which it can be entered, and—always—a mosque at its heart. Medinas are separated into quarters according to social and commercial hierarchies, with each quarter having its own communal oven, hammam (steam bath), and grocery shops within its network of streets and alleys.

Designated quarters: Craftsmen work in the areas of the medina known as souks, which were laid out according to the commodities being made and sold, with the most valuable products (such as gold and manuscripts) in the center and lesser goods radiating out from there. Today, little has changed, with each souk still named after the products sold there. For much of their history, Moroccan Jews lived in segregated mellahs—Jewish quarters—where they built homes, synagogues, markets, hammams, playgrounds, and cemeteries. The first one was established in a saline area of Fes in 1438 and named after the Arab word for salt: mellah. Subsequently, all Moroccan Jewish quarters were called mellahs. We’ll visit the souks and mellah in Fes, and have another opportunity to explore souks in Marrakesh.

Outside the cities: Before the 20th century, a foundouk was a caravansary, or roadside inn, used by traveling merchants. They slept upstairs, and on the ground level was a courtyard surrounded by stables for their camels, donkeys, and other livestock, as well as their goods for sale. We’ll see this layout at the Nejjarine Museum we visit on Day 4; it’s a restored foundouk. A casbah is a fortress-style building with crenellated defensive towers. In rural Morocco, representatives of the ruler lived in and governed from casbahs; a casbah can be inside a ksar (plural ksour), which is a fortified rural village surrounded by walls. Ait Ben Haddou, which we explore on Day 10, is a spectacular example of a ksar.

Archaeology and Urban Architecture

Morocco’s urban architecture spans more than 1,000 years of history; Fes’ Qaraouyine Mosque, which we visit on Day 4 of Camels to Casbahs, was built in the 9th century. Moorish design—with its horseshoe arches, floral motifs, and decorative plasterwork—arrived in the 11th century and has continued ever since; the Sadian Tombs, dating from the late 16th century are a magnificent example (we see them in Marrakesh on Day 11). Zellij tilework, with its mind-bendingly intricate geometric designs, came with the Merinids in the 13th century.

Modern era architecture includes Villes Nouvelles (modern towns) built outside the old medinas to protect them from development. Rabat’s Ville Nouvelle, built under the French Protectorate in the early 20th century, is one of Africa’s most ambitious modern urban projects. Casablanca’s Ville Nouvelle includes Art Deco and Art Nouveau influences. We’ll see examples of Morocco’s settlements, from pre-history to the present, as we visit many of the country’s spectacular UNESCO sites in Rabat, Volubilis, the Medina of Fes, Ait Ben Haddou, the Medina of Marrakesh, and the Medina of Essaouira.

Imperial Cities

Morocco’s imperial cities are its four historical capitals: Fes, Marrakesh, Meknes and Rabat; we’ll visit three of them on the Camels to Casbahs trip. Built for the king and his courtiers, these metropolises included impressive palaces and sophisticated irrigation systems, and reflected the rulers’ grand ambitions. Over the centuries, the capital moved several times among the cities of Rabat, Fes, and Marrakech.

Fes

Fes, the first and most evocative of Morocco’s imperial capitals, was founded in 789 by Idriss I, who established the Kingdom of Morocco. It served as the capital three more times as various dynasties rose and fell. Today Fes is resplendent with minarets and domes, and its renowned medina is one of the most perfectly preserved medieval cities in the world.

Marrakesh

Marrakesh was founded in 1071 and served as Morocco’s capital for the next two centuries, as well as in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is still considered a symbol of Morocco and a reminder of its powerful Almoravid and Almohad dynasties. With Berber, rather than Arab, origins, Marrakesh has been a central tribal marketplace for centuries.

Rabat

Rabat, the current capital, was occupied during Roman times and designed as an imperial city in the 18th century. Today this city of wide avenues and green spaces is Morocco’s second-largest city and the country’s administrative, financial, and political center.

Learn More

Talk to an Expert

Our Africa Specialists know every detail about our Morocco trips. They will be happy to answer any questions and help you choose the journey that’s right for you. Contact us to learn more or book your trip today!